In recent weeks, we’ve covered two of the three basic elements of creating a proper exposure in-camera—aperture and shutter speed—so let’s take a closer look at the third and final corner of the “exposure triangle,” known as ISO.

While your aperture and shutter speed settings will determine how much light enters your camera, ISO refers instead to the sensitivity of your film or your digital camera’s ability to capture light. In some ways, this is an oversimplification, but it works well for conceptualizing this term, especially in the beginning.

For most of photo history, ISO, and formerly ASA, served as a measure of “film speed.” Popular films frequently have their ISO values in their names. Kodak Ektar 100 has an ISO of 100, while Kodak Portra 400 has an ISO of 400, and so on. On film cameras, there’s usually a wheel that you can use to set your ISO to match the film you’re using.

Higher film speeds require less light to get the same exposure as a slower film.

The higher the number, the more sensitive the film will be to light. Fujifilm Fujicolor Superia 1600, for instance, requires much less light than Lomography Color 100 does to get a good exposure. More sensitive film stocks are called “fast films” because they don’t need a long exposure or a wide-open aperture to create bright photos.

For digital photographers, ISO works similarly. For convenience, the numbers are the same on your digital camera as they are for film, with common ranges varying from around 200 to 1600, though some cameras offer ISOs as low as 50 and as high as three million-plus (it’s true).

A higher ISO results in brighter images. The photo above was created at ISO 12,800.

Common values include 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, etc., with some cameras offering 1/3rd stops in between. You can usually change your ISO in your digital camera’s menu, though some models have designated ISO buttons. When we refer to a camera’s “base ISO,” we’re talking about the lowest native ISO setting; for most cameras, it’s usually around 100 or 200.

If you keep your other settings the same, changing your ISO will have a direct effect on how bright your photo is, just like it did in the days of film. ISO follows a simple, linear scale: ISO 800 is twice as sensitive (and requires half as much light) as ISO 400, which is twice as sensitive as ISO 200, and so forth.

You don’t need a high ISO to shoot in bright light.

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say you need a fast shutter speed to freeze motion and a narrow aperture for a wide depth of field. Maybe you’re photographing a sporting event or a bird in flight. You want everything in focus, without any blur, and as a result, you’re letting very little light into your camera.

If you’re shooting outdoors with lots of bright daylight, it might be possible to get a good photo with a lower ISO, but that same situation could easily result in underexposed images if you’re shooting indoors in low light. That’s where a high ISO comes into play, allowing you more flexibility in terms of shutter speed and aperture.

Concert photos are often shot at high ISOs due to low light. The one above was made at ISO 6400.

Similarly, for concert photography, you might be photographing a wedding at an indoor venue or a concert at night—everyone’s moving around, and the light is less than ideal. These are two cases where you’d have to bump up your ISO to brighten your images. If you switch from ISO 100 to ISO 200, you can then halve your exposure time or stop down and still get a proper exposure.

As we know, aperture and shutter speed affect your exposure, but they also have unique “side-effects”: aperture influences depth of field, and shutter speed changes the amount of motion blur in your photo. ISO also has a signature “by-product,” and that’s grain (film) or noise (digital).

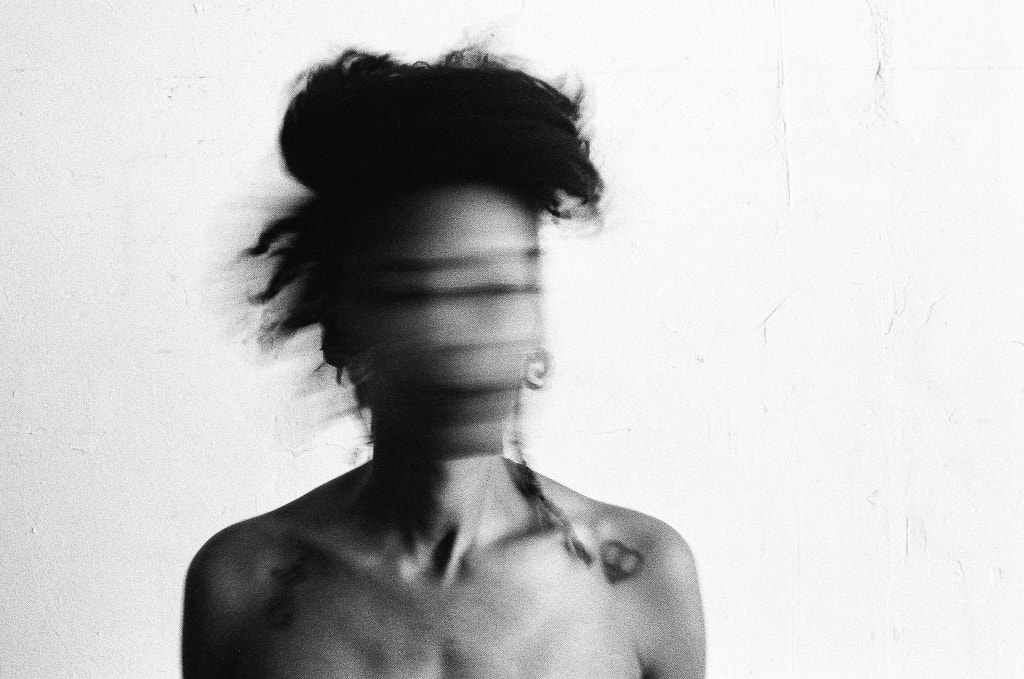

Film grain can add texture to your shots.

Film with a higher sensitivity has larger light-sensitive grains, resulting in that “grainy” look that’s so popular these days. If you look at black and white photos from the punk rock era, for example, you’re likely to see a lot of grain. That’s because those photographers were shooting at nighttime in low light with lots of active, moving people; they had no choice but to use a film with a fast speed and larger grains.

On digital cameras, bumping up your ISO won’t result in that textured, nostalgic grain but digital noise. You’ve seen noise before; it’s a distortion that can make your photos look splotchy or discolored. This loss of detail happens frequently with compact cameras and mobile phones because they have smaller sensors; that’s also why they have more trouble performing in low light than, say, a DSLR.

Landscapes with a long exposure time can generally be shot at lower ISOs, resulting in less noise.

If you view your photos at 100% or print on a larger scale, any noise issues will become apparent. This can be especially tricky with landscapes and large-scale portraits meant for exhibition. Luckily, modern cameras are getting much better at handling noise at higher ISOs, and post-processing software is also getting smarter about reducing noise as well.

As a general rule of thumb, though, you’ll want to keep your ISO as low as possible to avoid getting noise in your photos and degrading their quality, but as with aperture and shutter speed, it can be a subjective decision. You might love the grainy look you get with an old high-speed film like Ilford Delta 3200 Pro, and that’s a valid artistic choice.

Faster films produce more grain for a gritty, nostalgic vibe. The image above was shot with ISO 400 film.

On the other hand, if you’re shooting a portrait outdoors, there’s no need to introduce noise when you can just adjust your shutter speed or aperture to let in more light. Your choice of ISO depends on the conditions of your location, your access to additional light sources, and your style overall.

In low light, you might need a higher ISO.

For documentary and street photos, for example, it might not be necessary to avoid grain or noise completely—and adding grain can even add grit and texture—but for commercial product, portrait, and still life photos, you’ll want to keep your ISO low to preserve the highest possible quality.

Similarly, if you’re able to use a tripod for landscape photography, you’ll have the flexibility to use a longer shutter speed, so you might not need to boost your ISO at all. If, however, you’re shooting the milky way at night and want to get sharp pin-pricks of light rather than star trails, you’ll need a faster shutter speed, and therefore, a higher ISO.

Night photos tend to require a higher ISO, especially if you don’t want star trails. The photo above was shot at ISO 3200.

By switching to manual mode—or even aperture or shutter priority—you’re giving yourself more control over these three settings and determining the look, feel, and mood of the images you produce. Change one element of the exposure triangle, and you’ll be able to compensate for it using another.

The photo above was shot at an aperture of f4, a shutter speed of 1/6 seconds, and an ISO of 720.

In general, many photographers prefer to set their apertures or shutter speeds first, depending on the depth of field and motion blur they want, and then they set their ISOs at the lowest possible setting needed to get a good exposure with plenty of detail in the shadows. Juggling these three elements will help you get properly exposed, higher-quality images, and ultimately, they’ll also give you more creative license as an artist.

Not on 500px yet? Sign up here to explore more impactful photography.

The post What is ISO (and how to use it) in photography appeared first on 500px.

[NDN/ccn/comedia Links]

No comments:

Post a Comment